Uncertainty is where things happen. It is where the opportunities — for success, for happiness, for really living — are waiting. – Oliver Burkemen 1Popova, Maria. “Stop Overplanning: The Psychology of Why Excessive Goal-Setting Limits Our Happiness and Success.” The Marginalian, 5 Feb. 2014, www.themarginalian.org/2014/02/05/oliver-burkeman-antidote-plans-uncertainty/. Accessed 21 Apr. 2023.

Do a quick reflection exercise with me

Think back to some personal and professional goals you set 1-3 years ago. The more creative, the better.

For simplicity’s sake, pick just one goal. It might have been a creative project you wanted to finish, a career-oriented, wellness, or relationship goal.

Now try and recall when you were planning how to achieve that goal.

- How many actions did you think it would take to achieve?

- What sequence would those actions need to be in?

- How long did you think it would take to achieve that goal?

- What measurements were you using to see if you were on schedule with your goal?

Don’t worry if you forget most of what you were planning, but If you were to map out the goal planning visually, what did it look like?

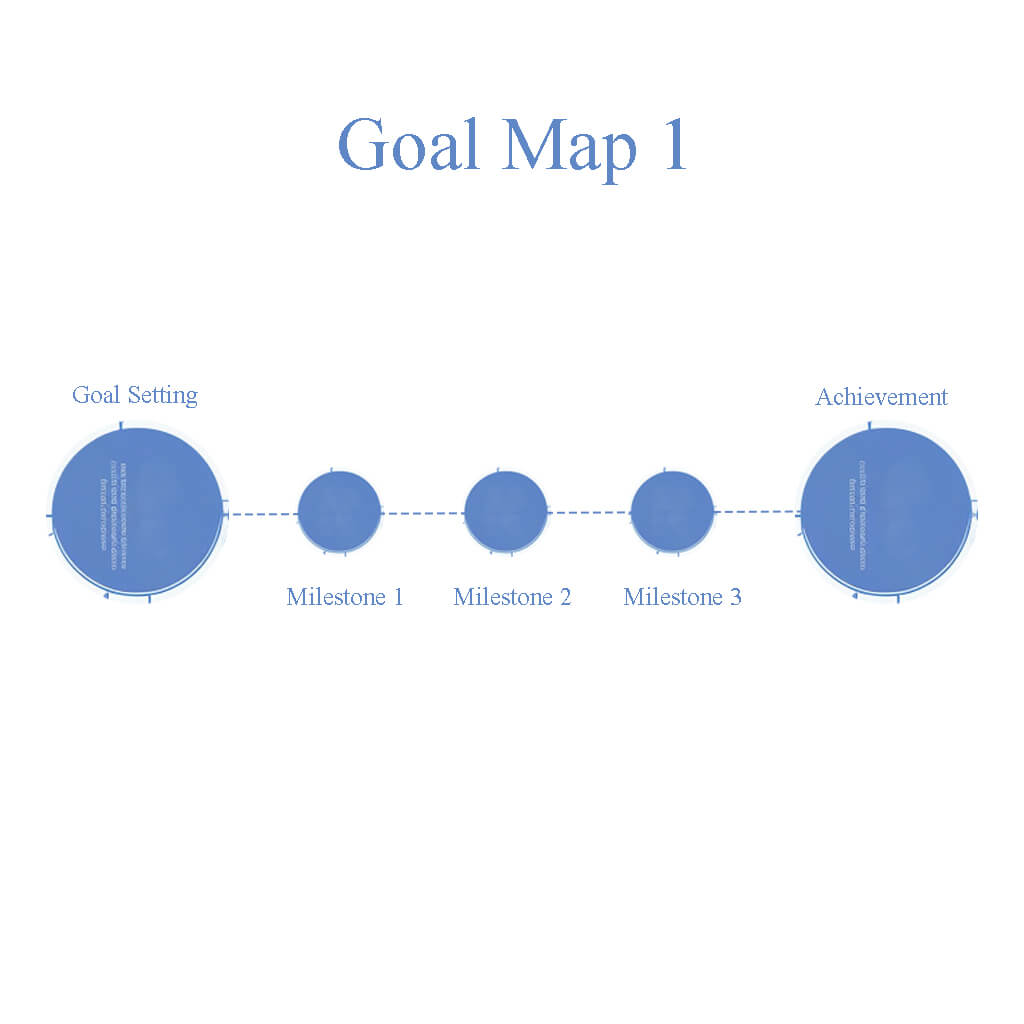

If you are a consistent goal setter or familiar with implementing best practices like S.M.A.R.T. goals, then it probably looked something like this.

Next, estimate how accurate your planning was. Don’t worry about being too precise. Just ask yourself –

- Did I achieve the goal?

- Did the goal change or have to be abandoned?

- Did achieving the goal take as long as I thought it would?

- Did it take more or less time than I thought it would?

- Did the tasks that I thought were necessary turn out to be necessary?

- Did I have to alter or abandon any of the tasks?

- Did anything that I couldn’t predict during the planning of the goal happen that affected the plan?

- Was I measuring the right things while working towards my goal?

What might it look like if you were to map out the actual path of action to attempt to achieve your goal?

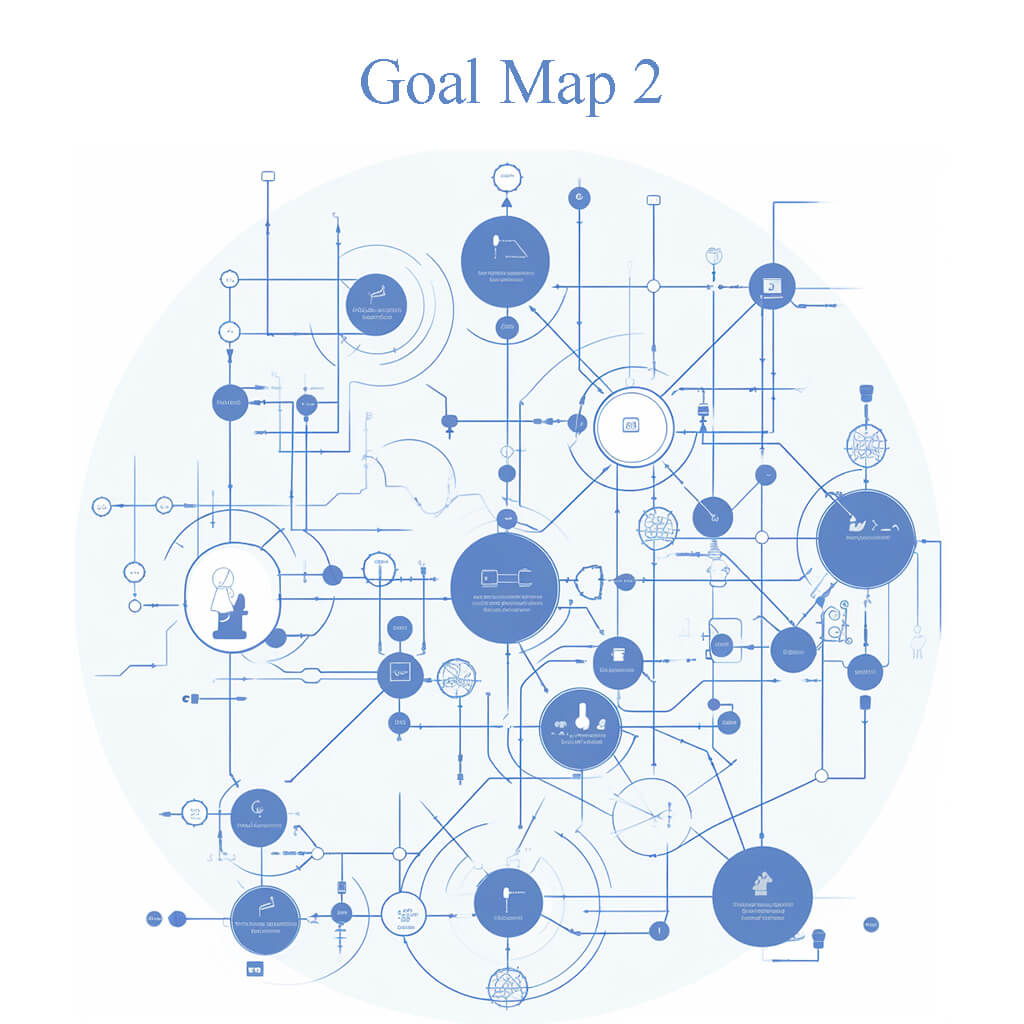

If you are being honest, no matter how well you planned things, it probably would look more like this.

Instead of looking to the past, look to your future and pick one creative personal or professional goal you want to achieve in 1-3 years.

Which type of map do you think the actual path to achieving that goal will look like?

Unless your goal is an exact replication of a previously accomplished one, I can almost guarantee the path to achieve it will look like Map 2.

The question then becomes, how the heck do you plan what it takes to achieve a goal like that?

The answer is you don’t.

Better yet, save yourself a lot of time and grief by ignoring goal-setting frameworks altogether.

Why? Because goal setting and planning aren’t effective for personal and professional growth, especially creative growth.

Let’s explore why this is and why what might look like chaos and disorganization in map two is a reason to celebrate, not feel anxiety and shame, especially when it comes to your growth and development.

Let’s also explore some ways that are much more likely to facilitate your development in a sustainable, balanced, and effective way.

What do you want to be when you grow up?

We are surrounded (particularly in the U.S.) by an intense culture of goal-setting and achievement.

From a very early age, we are taught to look to our future and envision what we want to have achieved in five, ten, or twenty years.

Imagine who you want to be in twenty years, dear kindergartner, and then work your way backward through life until you know what you are supposed to be doing today to make that vision happen.

If you can’t figure it out right now, that is okay. You have some time.

At least until middle school, where you will need to decide what electives to take, what extracurricular activities to pursue, and what sports to excel at so you can get into the right college, pick the right major, and then get the right job, which will start you on your right career path to become who you want to be eventually.

Your parents, teachers, and neighbors have some suggestions on what that looks like and how you should do this.

Confused by all this? Have serious questions? Skeptical of the plan? Want to explore other options? Then you must not be very serious about your goals. That, or you are flaky, lazy, not directed, and a slacker.

Not confused? Understand the plan? Got all of your future achievements, credentials, and accolades lined up and on your way to becoming what you want to be in ten years?

That’s great until the plan changes, your context does, something unexpected happens that makes the goal impossible, or you’ve learned some new information that makes the goal irrelevant. Then what?

All that anxiety and shame and confusion you feel is your fault because somewhere you didn’t set the goal right or plan well enough or execute the plan properly.

Don’t worry, though, I have a great book you might like that will help you:

Get the most out of your life!

Achieve the Impossible!

Win at life and dating and exercise and child rearing and your career and ping pong!

And it all starts with Goal Setting and Planning!

If this hits a little too close to home, you are not alone.

Goal setting and planning within non-specific, non-discrete spaces like “a life,” “a career,” or an “education” don’t work well because the entire concept of goal setting and planning wasn’t designed for it.

Goal setting: A motivational technique that works (sometimes).

Modern goal-setting theory and culture can trace their roots back to the turn of the 20th century when Fredrick Taylor, as part of the Scientific Management movement, espoused an approach to human labor based on “knowing exactly what you want men to do, and then seeing that they do it in the best and cheapest way.”2Frederick Winslow Taylor. Shop Management. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 1903.

The framework and philosophy then run through the research of Cecil Alec Mace who sought to explore the manipulation of direction, intensity, and duration of tasks to control the “will to work”. 3Carson, Paula Phillips, et al. “Cecil Alec Mace: The Man Who Discovered Goal-Setting.” International Journal of Public Administration, vol. 17, no. 9, Jan. 1994, pp. 1679–1708, https://doi.org/10.1080/01900699408524960.

The concepts of goal setting and planning were then further developed by Edwin A. Locke and Gary P. Latham, who describe their research intent as an effort to “predict, explain, and influence performance on organizational or work-related tasks.”4Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey.” American Psychologist, vol. 57, no. 9, 2002, pp. 705–717.

The more modern theories and practical applications of goal setting and planning have been tested and refined over the past decades and proven to be one of the most effective approaches to incentivizing human labor.

It’s no wonder that goal-setting and planning frameworks are proselytized by productivity bloggers, performance gurus, corporate consultants, and guidance counselors everywhere.

A detail seems to be missing in all this frantic effort to maximize potential, get more things done, and become the best you can be.

That detail is that the entire domain focuses on incentivizing standardized human labor.

The entire system was designed around testing performance within well-structured, well-understood, specifically constrained activities like simple games, typing performance, tree harvesting, and loading trees onto trucks. 5Latham, Gary P., and Edwin A. Locke. “Goal Setting—a Motivational Technique That Works.” Organizational Dynamics, vol. 8, no. 2, Sept. 1979, pp. 68–80, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0090261679900329, https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(79)90032-9. , 6—. “Toward a Theory of Task Motivation and Incentives.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, vol. 3, no. 2, May 1968, pp. 157–189, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0030507368900044, https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(68)90004-4. , 7Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey.” American Psychologist, vol. 57, no. 9, 2002, pp. 705–717.

Goal setting and planning is an incredibly effective approach to incentivizing actions that have:

- A predetermined and static endpoint.

- A precise understanding of the steps required to get to that endpoint.

- Clear rules and constraints, including well-established ways to measure progress.

- An environment that doesn’t change.

In design thinking, this environment type is often called “Kind” or “Well-Structured”.

Remember Map 1 from above. It visualizes goal setting and planning within a kind environment.

“Kind” problems “are definable and separable and may have solutions that are findable” 8Rittel, Horst W. J., and Melvin M. Webber. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences, vol. 4, no. 2, June 1973, pp. 155–169,

Chess, math, physics, and golf are all “Kind” environments full of “Kind” problems.

In golf, you can play a round, keep track of your score, make a minor adjustment, play another round, and test to see if that adjustment had an effect by comparing scores.

The rules, metrics, and constraints are standardized and won’t change from round to round, so this “Kind” environment is a great space to leverage goal-setting and planning.

Your personal, professional, creative, emotional, and intellectual development don’t operate within a “Kind” environment.

The development of your creative potential, no matter the domain, has and always will be happening in an environment where:

- There is no predetermined and static endpoint.

- There is no singular best step or action to move you forward.

- There are no clear rules or constraints.

- The environment is constantly changing.

These types of environments and the problems you try to solve within them are fundamentally different and are referred to in design thinking as being “Wicked”.

What is a Wicked Problem?

“Wicked Problem” is a term first used by Horst W. J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber in their article Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. 8

“Wicked,” in this case, doesn’t mean evil or malicious or nefarious. The term is used to classify environments and problems that have:

- no singular definition

- no defined endpoint

- a multitude of possible resolutions, and

- no solutions that could be defined by being true or false.

Education, crime, climate change, income inequality, and your creative development are all examples of “Wicked” environments full of “Wicked” problems.

All of that confusion about your goals? All that frustration about not having a clear, known path to become the person you think you want to be? All that anxiety and shame that happens when you thought you planned everything perfectly, and then it all fell apart? The nagging that you should be further along than you think you are?

That is all caused by trying to use frameworks designed for “Kind” environments with your “Wicked” ones.

As an experiment, let’s take a very popular and effective goal-setting framework and run a wicked problem through it.

S.M.A.R.T. Goals and Wicked Problems

If you have explored any level of productivity literature, you have probably run across the term S.M.A.R.T. goals.

S.M.A.R.T. goals are a framework created by George T. Doran in the early 1980s to help managers incentivize the performance of their underlings through a specific type of goal-setting approach that focuses on creating goals that are Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic, and Time-related. 9Doran, G.T. “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives.” Management Review, 1981, pp. 35–36.

The system does a very solid job of leveraging goal setting and planning theory and can be very effective for “Kind” problems, but let’s see what happens when we throw a “Wicked” problem at it.

Wicked Problem #1 – How do I Make Money with My Art?

It is a common question for creatives. How do I support myself financially through creativity and art-making? Let’s try and set a S.M.A.R.T. goal and see how it goes.

First, let’s pose the question as a goal.

“My goal is to be an artist who makes money with my art.”

Thousands of artists all over the world

Be More Specific!

“To be an artist who makes money with my art” is way too broad to be an effective goal.

Do we want to sell a single drawing to a relative for five dollars or become the most wealthy fine art painter the world has ever known? Both results would qualify as achieving our goal but would require massively different goal planning.

Let’s try and make our goal more specific by answering some relevant questions.

When we say “make money,” what do we mean?

- How much money? Seventy dollars? Seventy Million Dollars?

- Enough to live comfortably by yourself as a single 23-year-old in Malaysia?

- Enough to live comfortably and pay private school tuition for three kids in New York City?

Already you can see the wickedness of the problem rearing its head as it connects with other wicked problems like “How do I live comfortably in New York City?”.

When we say “with my art,” what do we mean?

- Photographic work expressing your obsession with baby ducks?

- Pet portraits of dogs created with oil paint and the shavings from their last haircut?

- Subway ads for Bitcoin?

One key thing to notice is that these questions have no true or false answers. You might choose what you think would be better or worse, but you won’t know the right answer because there is no singular right answer.

Could you live comfortably selling pet portraits? Maybe. You can’t know ahead of time.

If you are struggling with defining your goal specifically with clear answers to true or false questions or if in trying to get more specific, you find yourself with all sorts of questions with unknown answers, you are probably dealing with a wicked problem.

Maybe more clarity will come if we try to measure things.

Now Measure It.

What metrics might you use to know when you have achieved your goal? Just as important, what measures can you use to know that you are on track to achieve your goal?

In our case, money seems like an obvious thing to measure, but only if we determine a specific amount.

If our definition of “making money” is really about living comfortably in New York City, then given the changes in rent every year, that will be a moving target. We could arbitrarily guess and just say $100,000, but that brings up another issue.

How much art do I need to create to make $100,000? (another wicked problem).

If you are struggling to determine the relevant metrics that will get you to your goal, you are probably dealing with a wicked problem.

Next, Assign It!

The “assign” part of S.M.A.R.T. goals is pretty straightforward but reinforces that the system was designed around standardizing tasks and actions.

If a decision around assigning a goal must be made, then the goal must be standardized to be interchangeable between people. The goal won’t change based on who it is assigned to.

We’ve already started personalizing the goal by attempting to make it more specific. Your goal to make a comfortable living in New York by selling pet portraits is irrelevant and, therefore not assignable to someone else.

Is the Goal Realistic?

Estimating this depends on how you are measuring things and what type of specificity you chose, but the key thing to recognize is that we have no idea until we have achieved the goal.

Trying to determine how realistic things are is futile when navigating wicked problems because it assumes prior knowledge of what works and what doesn’t.

If you know ahead of time what will work and, therefore, what is realistic, then you are not dealing with a wicked problem.

Is making 69 million dollars with your “indiscriminately collated pictures of cartoon monsters…” realistic? Apparently so. 10Farago, Jason. “Beeple Has Won. Here’s What We’ve Lost.” The New York Times, 12 Mar. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/03/12/arts/design/beeple-nonfungible-nft-review.html.

Is becoming an “artist who makes money with their art” realistic? Maybe. Maybe not. You won’t know until you have done it (or have been unable to).

When navigating wicked problems like your creative and professional development, deciding what is realistic or not ahead of time limits your options and potential.

How Long Will It Take?

When can you expect the goal to be achieved? Wicked problems have no endpoint so you cannot know how long it will take.

How long might it take to “make money with my art”? It entirely depends on a multitude of factors, including many that you will have no control over.

Most Importantly, How Will You Get There?

I know some of you may still be skeptical and think you have the perfect S.M.A.R.T. goal for your wicked problem. You may look at the example and say:

“My goal is to be an artist who makes a comfortable living in New York City by making and selling 20 oil paintings a year at $30,000 a piece. I will complete this within five years.”

Great! That is a good example of using the S.M.A.R.T. goal framework to articulate a very ambitious, hypothetical, and fragile desired future state of being. It checks off all the goal-setting and planning boxes.

The next step is, working within the constraints of that goal. What is your 1st actionable step?

More importantly, what is your 301st actionable step? How will you test and measure in two months that your work will get you to your goal? If, in two months, you are ahead of schedule, what will you do? If you are behind schedule, what will you do?

What happens if the art market crashes? What happens if you break a finger playing pickleball and have to hold off on painting for eight months? What happens if, in year two of your plan, all oil paint manufacturers shut down production because of technological disruption?

What happens if an opportunity presents itself that allows you to make a comfortable living in New York City but doesn’t involve painting?

In my twenty-five years of teaching creatives, I have never met one whose Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic, Time-based creative and professional goals survived first contact with life (myself included).

The more specific, measurable, and time-based your goal, the more fragile it and its planning become.

So what do we do?

Do we try our best and see what happens? Do we settle for finding the nearest “Kind” environment to work in?

Absolutely not.

When I encourage ignoring goal-setting and planning for your creative and professional growth, I do not mean for you to “just wing it” or “just start working and see what happens!”.

Direction and focus are essential, and there are approaches to exploring your “Wicked” environments in a way that is connected, balanced, flexible, and way more effective than traditional goal-setting and planning.

It starts with ditching goals and setting intentions instead.

What is the difference between goals and intentions?

Goals describe a discrete, desired future state of being.

Intentions articulate a conscious commitment to action in a direction that empowers exploring your interests.

If a goal is an X representing a specific destination on a treasure map, an intention is a compass allowing you to explore that map.

This is important because, with wicked problems like your creative and professional development, there is no X.

Actually, there is no map.

You will create the map as you explore the landscape around you.

The Strength of Intentions

Intentions share some of the very qualities that make wicked problems so vexing. They work in confluence with wicked problems instead of trying to tame them.

A small sampling of the strengths of intentions:

- There is no true or false intention. They work on a spectrum of better or worse depending on the context.

- There is no endpoint to an intention. You can ignore it or abandon it, but there is no end of the road or solution to an intention.

- Intentions incentivize a confluence of action while allowing for a multitude of paths to explore.

- Intentions have no time constraints. They can be applied to your next hour or your entire life.

- Intentions have a bias toward present action instead of a future state of being.

- Well-designed intentions build a clear and direct bridge between your values and actions.

The Weakness of Intentions is Actually a Strength

The largest weakness of intentions is that they lack the force of action that goal-setting and planning have.

The “why” of goal setting isn’t setting goals for the sake of it.

Goals are designed to incentivize action along a specific, known path as efficiently as possible.

Goal A is reached by completing specific action 1, then 2, then 3. If you have Goal A, you know it is time to start action 1. When you finish action 1, you know it is time to start action 2.

With intentions, there is no obvious and linear next step.

Knowing what direction you want to head doesn’t necessarily mean you know how to head in that direction.

However, this weakness is a strength because an intention’s lack of connection to a specific path of action means that it can be leveraged within a multitude of approaches to action.

- Combine intentions with effective project design and management, and your creative and professional growth will skyrocket in ways you cannot predict ahead of time.

- Combine intentions with effective habit design, and you will feel more in control of your day than you thought possible, no matter what sort of disruptions occur.

- You can even leverage intentions with goal-setting within “kind” environments. This will help connect the desired state of being with the “why” of a desired state of being.

Combine all three plus any other way you want to approach getting things done, and you will start to create powerful confluences between what initially seemed like disparate activities.

That confluence will supercharge your growth within “Wicked” environments like your professional, personal, and creative growth.

Not only will your growth skyrocket, but it will do so in an agile way while staying connected to your core values and interests.

This connection means that every intention you design will be personalized and allow for complete autonomy in how you design them.

As a bonus: The process by which you design your connected, meaningful, and personalized intentions is less complicated than traditional goal-setting and planning.

Interested in learning how to design and manage effective and meaningful intentions?

Intention design is an easy skill to start learning, but it takes time and practice to master and internalize.

If you are interested in getting a head start with leveraging the power of Intention Design, I hope you will join me for Intention Design for Creatives.

Intention Design for Creatives is a unique digital learning experience that will guide you as you create an agile and personalized Intention Design and Management system.

By the end of this learning experience, you will have a better understanding of how intention design can benefit your creative development through a framework of action that will close the gap between your values and the creative work that allows you to explore and develop those values in a balanced and intentional way.

You will also apply the principles you learn through an agile digital system that will develop over time as you use it.

The features include:

- A multi-lesson, interactive mini-course that delves into the principles and practices of effective Intention design and management.

- The Intention Design for Creatives Notion.so template that leverages the principles you’ll learn in a way that will grow and become more personalized as you use it.

- A subscription to the Antifragile-Creative Newsletter

Fill out the form below to get started free of charge.

Footnotes

- 1Popova, Maria. “Stop Overplanning: The Psychology of Why Excessive Goal-Setting Limits Our Happiness and Success.” The Marginalian, 5 Feb. 2014, www.themarginalian.org/2014/02/05/oliver-burkeman-antidote-plans-uncertainty/. Accessed 21 Apr. 2023.

- 2Frederick Winslow Taylor. Shop Management. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 1903.

- 3Carson, Paula Phillips, et al. “Cecil Alec Mace: The Man Who Discovered Goal-Setting.” International Journal of Public Administration, vol. 17, no. 9, Jan. 1994, pp. 1679–1708, https://doi.org/10.1080/01900699408524960.

- 4Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey.” American Psychologist, vol. 57, no. 9, 2002, pp. 705–717.

- 5Latham, Gary P., and Edwin A. Locke. “Goal Setting—a Motivational Technique That Works.” Organizational Dynamics, vol. 8, no. 2, Sept. 1979, pp. 68–80, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0090261679900329, https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(79)90032-9.

- 6—. “Toward a Theory of Task Motivation and Incentives.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, vol. 3, no. 2, May 1968, pp. 157–189, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0030507368900044, https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(68)90004-4.

- 7Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey.” American Psychologist, vol. 57, no. 9, 2002, pp. 705–717.

- 8Rittel, Horst W. J., and Melvin M. Webber. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences, vol. 4, no. 2, June 1973, pp. 155–169,

- 9Doran, G.T. “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives.” Management Review, 1981, pp. 35–36.

- 10Farago, Jason. “Beeple Has Won. Here’s What We’ve Lost.” The New York Times, 12 Mar. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/03/12/arts/design/beeple-nonfungible-nft-review.html.